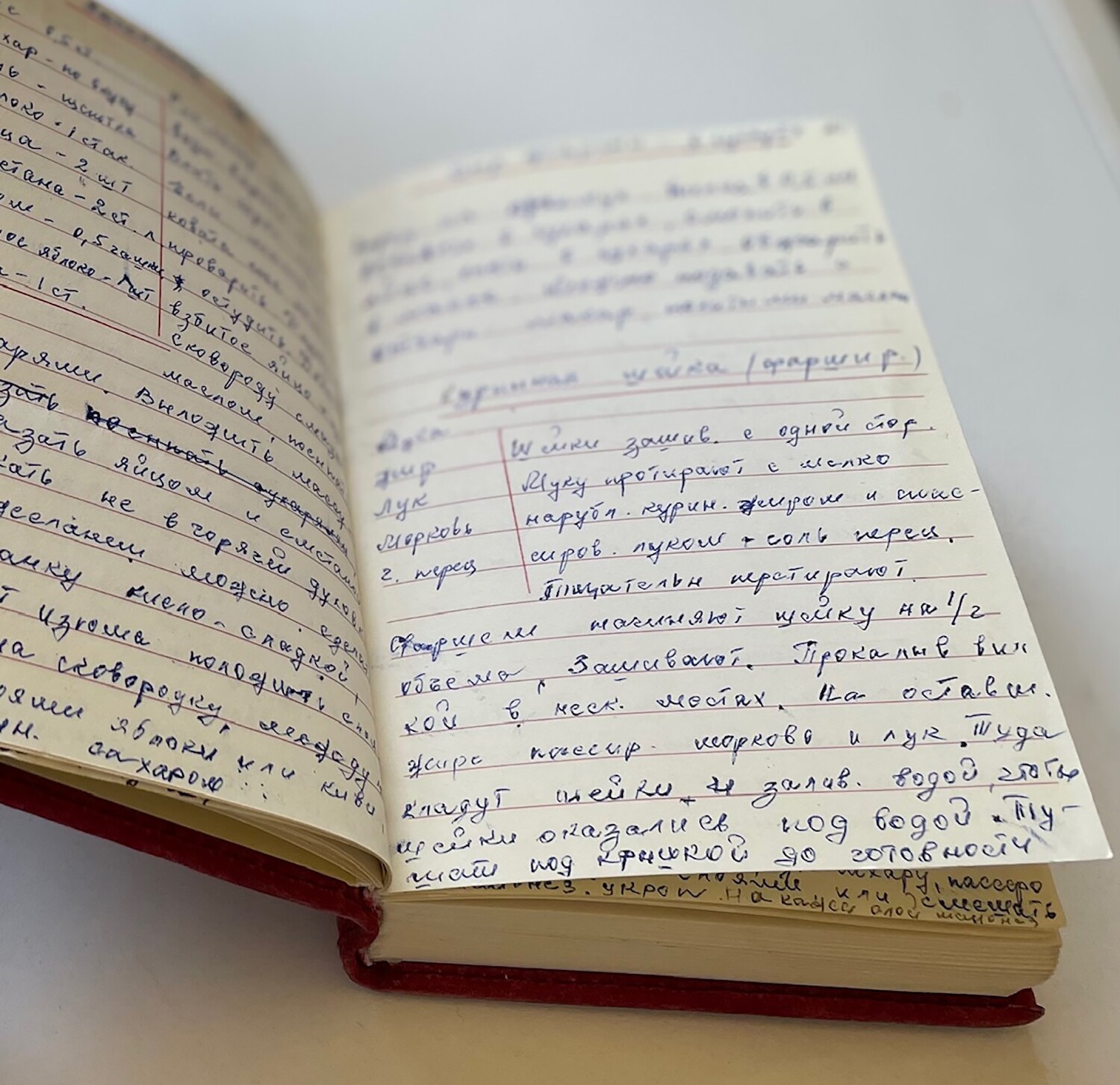

“Sew the necks up on one facet. Combine flour, fried onions and hen fats and stuff the necks.”

This can be a line from a pocket book through which my grandmother wrote out household recipes for me by hand, a number of years earlier than she handed. It comprises directions for dishes that sustained my ancestors in Ukrainian and modern-day Belarusian cities and cities for generations.

The pocket book has a burgundy velvet cowl and a floral embellishment that was glued on by my grandfather. My mom’s dad and mom purchased it whereas looking a storage sale, certainly one of their hobbies after we arrived in America as refugees fleeing antisemitism and a crumbling Soviet Union. Storage gross sales gave them a possibility to apply English with American neighbors and to marvel on the trinkets they’d by no means seen in the united statesS.R. or couldn’t afford: a cleaning soap sculpture of a woman in a elaborate hat for 1 / 4, an actual silver ring for 50 cents (“Are you able to consider it!?”), an enormous portray of a lake for a greenback.

The recipes have taken on a brand new which means since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. I now preserve the pocket book close to me, rereading the phrases of my grandmother who was born in Vinnytsia, Ukraine, and lived via Stalin’s Holodomor genocide within the Nineteen Thirties, adopted by the Holocaust.

Typically I browse for meal concepts, like her recipe for chopped liver or vareniky (Ukrainian dumplings) or pickled cabbage and cucumbers, a staple of Jewish shtetl life in Jap Europe. Different instances I stare at her trainer’s shorthand, searching for consolation in its neatness, or anxiously seek for random issues — a Yiddish phrase, for example, amid the Russian, or the handwritten desk of contents with a squiggly 7 — simply to verify they’re nonetheless there.

I preserve returning to her recipe for “stuffed hen necks,” a poor man’s delicacy that usually has no neck in it in any respect. It’s a craft undertaking: Pores and skin the hen, make a pouch out of the pores and skin, then stuff it with a mix of fried onions, hen fats, flour (or farina) and, if you happen to’re fortunate, giblets.

“Hen necks” is a festive and scrappy dish, having sustained Ashkenazi Jewish households for generations, even extolled by Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem in his 1902 quick story “Geese.” Nothing, not even the fowl’s pores and skin or abdomen, ought to go to waste. “Sew them up,” my grandmother writes. Then boil, slice and serve.

As a baby, I bear in mind watching each my grandmothers stitching up the bumpy translucent hen pores and skin with a needle. The sight turned me off the ultimate product for years, till not too long ago.

The pocket book additionally has trendy recipes, from the Soviet period, beset with meals shortages. There’s “Mimosa salad,” an appetizer long-established out of canned fish and boiled egg, masking with its sprightly identify the simplicity of the components. And “vacation potato”: Boil a potato in beet water until it’s pink.

That is the way you make bread last more, explains my grandmother: Separate rye and wheat loaves and wipe the breadbox with vinegar and water a minimum of as soon as per week. That is the way you take away mould from pickled cucumbers, instructs the matriarch who nourished 4 generations residing in a two-bedroom Soviet residence.

Some recipes don’t have ingredient portions. You make do with what you’ve bought.

As I leaf via the pages of acquainted dishes, I’m flooded with recollections: the sizzle of frying onions, the candy tangy perfume of borscht on the stovetop and my grandmother’s tales. She usually advised us about her escape from the advancing German military as a teen throughout World Warfare II. Her household grabbed what they might carry and ran to the practice station. Because the practice, packed largely with ladies and youngsters, carried them east, it was nearly hit throughout an air raid. A practice behind them caught fireplace. She needed her youngsters and grandkids to grasp the horror of conflict, and the significance of gratitude and remembering one’s historical past.

I verify my cellphone for the newest information out of Ukraine, the place the conflict exhibits no indicators of abating. The tales are eerily similar to these I grew up listening to, besides the offensive is now carried out by Russia, and it’s 2022, not 1941.

Again then, my grandmother evacuated, however her ailing grandparents couldn’t. They had been slaughtered by the Nazis, together with hundreds of different Vinnytsia Jews. She carried the invisible scars for the remainder of her life. She at all times stocked up on canned items. She panicked after I was a couple of minutes late from enjoying outdoors.

If she had been nonetheless alive, how would I clarify Russia’s conflict? That her beginning nation is being bombed by the nation she stayed in after World Warfare II and the place I used to be born. That our relations in Ukraine not too long ago fled from Vladimir Putin’s advancing forces. That our relations in Russia had been arrested and jailed for protesting. That historical past is repeating.

I’ve no solutions. However as I learn between the traces of the little recipe guide, I see survival suggestions and immense reserves of power.

In spite of everything, its knowledge has for generations withstood famines and grain theft. Pressured assimilation and the gulag. Bloodthirsty dictators with their sights set on empires. I’m furiously powerless to cease this conflict. However forgetting is just not an choice. As a small act of resistance, I head to the kitchen, to cook dinner.

Masha Rumer got here to the U.S. together with her household when she was 13. Her guide “Parenting With an Accent: How Immigrants Honor Their Heritage, Navigate Setbacks and Chart New Paths for Their Youngsters” was revealed in November.